The Pullman Building

You are at Home -> The Company -> Charles W. AngellCharles W. Angell

With its inception, Charles Angell joined Pullman's Palace Car Company (PPCC) as Secretary, which included duties as secretary to the PPCC Board of Directors. He initially worked with George Pullman's brother Albert, who handled day-to-day operations while George traveled visiting railway execs and promoting his rail cars. [1] Angell kept Pullman well-informed as he traveled, e.g., sending George a letter that the PPCC had purchased the Detroit Car and Manufacturing Company for $100,000 in September 1870 and traveling himself to Detroit to settle with the stockholders of that company. [2] If George Pullman can be said to have been close to any of his employees, the Angell brothers (Charley's brother, William A. Angell, also worked for the PPCC as Purchasing Agent, and had originally come to Chicago with him from the East) were it. In the early 1870s Charley became ill and Pullman gave him $500 before he left on a two-month vacation to regain his health. [3] From later scathing editorials, one can glean tidbits about his personality and foibles: His dress was faultless. That is to say, it was neither too rich nor too gaudy; it was the style of the millionaire who feels that personal adornment can add nothing to his importance. In the matter of kid gloves he was lavishly extravagant; it is related of him that he never drew on a pair the second time. Possibly this is an exaggeration. He scorned Mother Earth as heartily as he despised street-cars and soiled kid gloves. As he would not tread upon common pavements, nor mingle with the common heard in a five-cent public conveyance, he was compelled to indulge in the expense of a private carriage. Hence, as he was punctilious in the observance of society obligations, his coupe was often seen at the doors of the fashionable residences of the “upper ten.” No grand party was complete without the presence of Angell, who threaded his way through the dense throng with a gloomy air of abstraction recalling to mind the character of Hamlet. [4] In a slightly earlier Tribune article, an episode from ten years previous was related:Angell had some peculiar idiosyncrasies. It is said of him that he was at times cross and overbearing to those with whom he came in contact, but it was laid to the fact that he worked hard, and that he had troubles of the heart, which caused him at times to become morose. About ten years ago the … Secretary left one day rather suddenly, and nothing was heard of him for three weeks…after a time he turned up in an interior town in New York State. He claimed then to have been insane, and had no recollection of how he came to go away, or how he got to the point where he was discovered…a critical examination of his assets developed a large drawerfull of kid gloves, each pair evidently not having been worn more than once…During the past year Mr. Angell was remarkable for the elegance of his attire. Button-hole bouquets adorned the lappel [sic] of his coat, and his hair was always carefully parted in the middle. [5] A 1873ish, Angell married one of the great beauties of Chicago, Eva Badger. [6] However, Angell's wife died in childbirth in 1875, along with one of the twins she was bearing, and Angell was bereft; friends feared for his mental and physical health. [7] By 1877, he was presumably recovered, a respectable widower with child; but when he asked another woman to marry him in 1878 and she refused, “he began leading a more dissipated life, though he was neither a gambler nor a drinker.” He may have even spent a period of time with a woman from one of Chicago's famed and numerous houses of ill repute. [8]

Robbery!

On July 24, 1878, Charley withdrew $1,200 from the company account (leaving PPCC stock he owned as security); told his office and the cashier that he was going on an extended vacation (though he would meet George Pullman in New York); and asked that mail not be forwarded. [11] What was not yet known was that he also helped himself to about $50K given to him in checks (bypassing company policy with the cashier in providing vouchers), and about $70K in securities and bonds owned by the PPCC (he may have been snitching securities for awhile), which he sold in New York. [12] He was last seen in New York on July 26, 1878. When George Pullman returned from Europe on August 7, it became apparent that something was wrong. Angell did not meet him and had left no address where he could be reached. Concerned because the Chicago office had indicated Angell might be ill, Pullman dispatched brother William to various places where Charley had said he would go, or to which he had been before, to no avail. [13] Pullman then returned to Chicago:It seems also that Mr. Angell's absence from the office of the Company here without leaving any address, or communicating in any way with any of his associates…excited some comment, which being communicated to me, added somewhat to my apprehensions, and I immediately came to Chicago and instituted a thorough examination. This developed the fact that Mr. Angell had disappeared with funds and securities of the Company. The amount taken by him, although considerable, is not sufficient to occasion the Company any embarrassment, nor interfere with its regular business or dividends… …The Company is already taking the most vigorous measures for Mr. Angell's apprehension, and proposes, if possible, to recover the bonds and securities abstracted by him; but, for obvious reasons, the measures adopted cannot be made public. [14] Although it could have been assumed that Angell had taken a boat to some unknown European location, the Pullman Company spent a few months looking in the United States. It was actually not until September that somebody had the bright idea to issue circulars offering a reward for Angell's arrest and detention. [15] They also issued a second page listing the numbers of the coupons and bonds Angell had stolen. These included 24 U.S. Government 4% bond coupons and 25 Chicago and Alton Railroad “6% Gold Sinking Fund Bonds of $1,000 each”. [16; also see sidebar] At least 100,000 “wanted” circulars were printed and distributed throughout the world, especially to U.S. Consulates, in five languages: English, French, Italian, German, and Spanish. Each circular included a picture, a fairly uncomplimentary description, and a description of Angell's luggage. [see sidebar below] Packets of circulars were accompanied by a letter from PPCC Vice President Horace Porter: Dear Sir. I take the liberty of sending you some circulars and pictures which explain themselves, and shall be greatly obliged if you will kindly retain a copy and place the rest in the hands of the police authorities in your vicinity or such persons as may be specially charged with the detection of criminals. Should the person named in the circular be found in your neighborhood you will render us a great favor by taking immediate steps towards his apprehension and telegraphing to this office of the discovery. Yours very truly,

Horace Porter

Vice Pres't. [17]

Capture & Return

The hundred thousand flyers paid off, although the PPCC had to deal with numerous false sightings. But on November 1898, the Company received a telegram from the American Minister in Lisbon, Portugal, indicating that the whereabouts of Charles W. Angell had been discovered. Shortly thereafter, on November 21, he was identified (having been living under the assumed name of Seymour and with a British passport) and arrested. [18] The Portuguese commissary of police came to Mr. Angell's room in the hotel [Hotel Central], where he had lived a most secluded life for a few days, being practically laid up with rheumatism. The commissary general said, without introducing himself: ‘Mr. Seymour, will you allow me to look at your passport?”…Then the commissary general suggested Seymour had better go up then with them to the civil governor's, to which the stranger acceded at once. As he went out of the door of his room the presence of two officers outside and a third at the bottom of the stairs showed him that THE DAY OF RECKONING had come… [19] Angell's identity confirmed, authorities returned with him to his room where they examined his trunk and its contents, including a case on top. The case referred to was found to contain THREE PACKAGES OF BONDS of a value of $25,000 each, United States Bonds, Chicago city bonds, and Alton and St. Louis railroad bonds. There were also 1,000 pounds in English paper and gold, making in all $80,000. He had but little jewelry, not being a man of extravagant tastes. He had spent the difference between $80,000 and $120,000, in speculations during the three years the peculations had been going on, which had been altogether since the death of his wife, three years ago…He had only been at the hotel eight days when apprehended. He was then taken to the city jail and incarcerated. He had originally sailed from New York in a German steamer to Southampton, where he took out an English passport. Then he sailed with this on one of the Royal steamers for Rio. Here he remained for three weeks, and then sailed in one of the same line of steamers to Lisbon. [20] Newspapers of the time made much of the fact that the United States at that time had no extradition treaty with Portugal and that a number of criminals had made their way there; however, friendly relations were assumed to engender good cooperation by the Portuguese Government which turned out to be the case. [21] Angell himself was moved to remark, “I knew all along that the absence of any extradition treaty would not be worth a sou to me.” [22] Nonetheless, the gathering of official papers and the slow travel by steamer meant that Angell did not start back to the states with his escort until January 1879 and did not arrive in the United States until February. Angell spent the voyage unconfined, playing seven-up with the Captain, reading (being especially fond of Byron and Shakespeare) from the Captain's library, and keeping a verbose, minutely detailed, and sometimes amusing log of the voyage. An excerpt: Our crew were well-behaved and performed their duties in a commendable manner. They were prompt to their meals and turned in at eight bells with an alacrity that never ceased to attract the attention of their captain and reassure his pride in them…The second mate is of Hibernian [Irish] extraction, with a pugilistic attitude toward the steward, a good sailor, and sleeps well after each watch. The first mate is Teutonic, and murders the king's English without mercy. In good or bad weather his appetite fails him not, and he slaughters the food set before him as badly as he does our language. [23] Upon arrival in the United States (Delaware), Angell was escorted to a train for the trip to Chicago, where he arrived February 25, 1879: At 10 o'clock, Charles W. Angell, the magnificent, stepped from a Pullman palace car at the Archer avenue deport of the Fort Wayne Road, escorted by Capt. Whitney Frank…The twain entered a carriage which was in waiting…Half an hour later Angell was placed behind the bars of the County Jail, and given Cell 43, which will be remembered as the one which was occupied by Sherry, the murderer. [24]Jail: “Angell Joliet”

I am anxious to satisfy the law and atone for the crime I have committed; that is all. I am in no wise perverse in the matter, I assure you; but simply rightly determined, as I believe. [33] Angell was delivered to the Joliet Penitentiary shortly after his trial, and at least one letter to the editor to the Chicago Tribune at the time crowed in a self-satisfied moral tone about the just sentence imposed on the felonious embezzler who betrayed such a sacred trust: “The career of Angell and its gloomy climax in a great crime constitutes a terrible warning warning against habits of thought which tend to self-deception, and hence to promote utterly false views of life, its duties and responsibilities….His character is so singular…that we shall watch with some interest his course in the penitentiary.” [34] An editorial on the same day noted “In the midst of so many similar instances of commercial dishonor and flagrant breaches of trust, it is cheering to record that in one prominent instance justice has been administered and a penalty somewhat adequate to the enormity of the offense will have to be suffered.” [35] But by 1883, the Tribune began printing articles with a different tone. In January, a reprint from the Rockford Gazette added a few details and a different perspective, as an initial call for Angell's pardon: When his case was called he rose and plead guilty, and then bowed his head low, asking to be sentenced. No expense was caused the State; and the Judge—Judge Williams—did sentence him cruelly to hard labor in the penitentiary for the longest term authorized by the statute. This was a cruel sentence, and it was likewise a corrupt one. …Judge Williams was a candidate for reelection, and by yielding to the momentary clamor of the crowd expected to make many votes…Now Judge Williams expresses sorrow for the sentence he pronounced; the State's-Attorney recommends that he be pardoned; Mr. Pullman and many of the best men in Chicago unite in this recommendation; and why is he not pardoned instantly? [36] The governor of the time, Governor Cullom, had apparently refused to consider papers requesting Angell's pardon several weeks before, although he apparently pardoned a “vulgar criminal.” [37] Alas for poor Charley: “His services have been of great value to the State. The books and financial affairs of the penitentiary have been almost wholly under his hand and direction. No complaint has he ever uttered, no labor shirked. But the sense of mortification has been all but overwhelming, and now he is worn, gray, and half-blind. Handsome, brilliant Charley Angell how sad and inevitable the change that has come over you in these four dark years!” [38] In July, a Tribune reporter got down to Joliet to talk to Angell about the whole idea of the pardon, which Charley was quick to point out he had not initiated. Here we also learned that he was actually bookkeeper for contractors E. R. Purington & Co. and the Burlington Marble Factory, “a large part of their cut-marble work being done by convicts. The State is paid 55 cents a day by the contractors for the services of Mr. Angell, while they concede his work is valued at not less than $5 a day for each of the two houses for which he keeps a set of books.” [39] The reporter also indicated Angell was in charge of the prison library, cataloged and indexed the books, and hounded the printer of the catalog to get them there before the following Sunday. [40]Epilogue

So what happened to Angell? On a curious note, the 1900 Census lists Charles W. Angell, aged 61, as residing at the State Penitentiary, Will County, Illinois, more than 10 years after his original sentence would have been completed. One wonders if he was cooking some books, or whether he continued in bookkeeping employment after his sentence was served. The 1910 census lists him, at age 70, in Cook County. I could find no local obituary for Charles, although William Angell died after a long illness on November 15, 1916, having retired twelve years before (see sidebar). And despite the black-sheep transgressions of Charles, William was remembered with $10,000 in Pullman's will when he died in 1897. [41] The Pre 1916 Illinois Statewide Death Index lists Charles W. Angell, aged 74, as dying on November 1, 1913.Notes

- [1] Liston Edgington Leyendecker, Palace Car Prince: A Biography of George Mortimer Pullman (Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1992), 84.

- [2] Leyendecker, 149.

- [3] Leyendecker, 159.

- [4] “Angell,” Chicago Tribune, February 26, 1879, 4.

- [5] “Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, August 19, 1878, 5.

- [6] Carter H. Harrison, “A Kentucky Colony,” in Chicago Yesterdays: A Sheaf of Reminiscences, ed. Carolyn Kirkland (Chicago: Daughaday & Company, 1919), 174. See also Leyendecker, 159.

- [7] Leyendecker, 159.

- [8] Leyendecker, 159-60.

- [9] “Dom Pedro,” Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1876, 8.

- [10] “Loan Agencies,” Chicago Tribune, October 31, 1875, 8.

- [11] Leyendecker, 160.

- [12] Ibid. See Also George Pullman, Letter to the Editor, Chicago Tribune, August 18, 1878, 3.

- [13] Pullman, Letter to the Editor, 3.

- [14] Ibid.

- [15] Leyendecker, 160.

- [16] Pullman's Palace Car Company Caution Circular, Pullman Company Archives, Newberry Library; George M. Pullman Files, 1867-1897, Box Box 1, Folder 2.

- [17] Horace Porter, General letter to accompany Angell circulars, September 20, 1878. Pullman Company Archives, Newberry Library; George M. Pullman Files, 1867-1897, Box 1, folder 2.

- [18] “Angell,” Chicago Tribune, undated clip from Pullman Company Archives, Newberry Library, George M. Pullman Files, 1867-1897, n.p., n.d. but probably November 21 or 22, 1878; also “Angell's Arrival,” Chicago Times, February 23, 1979, n.p.

- [19] “Angell's Arrival,” Chicago Times, February 23, 1879, n.p.

- [20] Ibid.

- [21] “Angell,” Tribune, November 1878. See also “Criminal News,” Chicago Tribune, November 30, 1878, 5; and “Angell's Arrival,” Chicago Times, February 23, 1979.

- [22] “Angell's Arrival,” Chicago Times, February 23, 1879, n.p.

- [23] Ibid.

- [24] “Angell,” Chicago Tribune, February 26, 1879, 5.

- [25] Ibid.

- [26] “Criminal News,” Chicago Tribune, February 25, 1879, 5.

- [27] “Angell's Sentence,” The Daily Inter-Ocean, Friday, February 28, 1879, n.p.

- [28] Ibid.

- [29] Ibid.

- [30] “Angell's Sentence,” The Chicago Evening Journal, Thursday, February 27, 1879, n.p.

- [31] Ibid.

- [32] “Charlie's Choice,” Chicago Times, Friday, February 28, 1879, n.p.

- [33] Ibid.

- [34] “Exit Angell,” Chicago Tribune, February 28, 1879, 3.

- [35] Editorial, Chicago tribune, February 28, 1879, 4.

- [36] “Charles Angell: A Strong Plea for His Pardon,” Chicago Tribune, February 2, 1883, 9.

- [37] Ibid.

- [38] Ibid.

- [39] “An Angell Visitor,” Chicago Tribune, July 27, 1883, 8.

- [40] Ibid.

- [41] “Pullman Will is In,” Chicago Tribune, October 28, 1897, 1.

THE PULLMAN HISTORY SITE

Contributed by Kate Corcoran

Charles W. Angell, from his “Wanted” poster, 1878. Note the bouquet in his lapel. From a copy, Pullman Company Archives, Newberry Library, George M. Pullman Files, 1867-1897, Box 1, folder 2. Despite various incidents of mental illness or insanity, Angell was occasionally the PPCC spokesman, and he was assigned high-level tasks, especially when George Pullman was out of town. For example, he met the train for Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro d'Alcantara as he made a flying trip through Chicago. [9] Angell was also the president of the People's Building and Loan Association, along with a J. Sanger (relative of Hattie's, perhaps?) in 1875; the capitalization for the company was about $1,000,000. [10] We have not yet discovered if George Pullman was involved in this business.

Internet found image of The PPCC wanted circular offering a $5,000 reward plus 10% of money recovered.

Listing of bonds stolen by Charles Angell; copy of flyer issued by PPCC September 1878, from Pullman Company Archives, Newberry Library, George M. Pullman Files, 1867-1897, Box 1, folder 2.

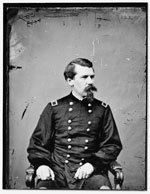

Horace Porter in a photograph taken between 1860 and 75. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

Other Pullman-Related Sites

- Historic Pullman Garden Club - An all-volunteer group that are the current stewards of many of the public green spaces in Pullman. (http://www.hpgc.org/

- Historic Pullman Foundation - The HPF is a non-profit organization whose mission is to "facilitate the preservation and restoration of original structures within the Town of Pullman and to promote public awareness of the significance of Pullman as one of the nation's first planned industrial communities, now a designated City of Chicago, State of Illinois and National landmark district." (http://www.pullmanil.org/)

- The National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is a 501(c)3 cultural institution. Its purpose is to honor, preserving present and interpreting the legacy of A. Philip Randolph, Pullman Porters, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the contributions made by African-Americans to America's labor movement. ((http://www.nationalpullmanportermuseum.com/)

- Pullman Civic Organization - The PCO is a strong and vibrant Community Organization that has been in existence since 1960. (http://www.pullmancivic.org/)

- Pullman National Monument - The official page of the Pullman National Park. (https://www.nps.gov/pull/)

- South Suburban Genealogical & Historical Society - SSG&HS holds the Pullman Collection, consisting of personnel records from Pullman Car Works circa 1900-1949. There are approximately 200,000 individuals represented in the collection. (https://ssghs.org/)

- The Industrial Heritage Archives of Chicago's Calumet Region is an online museum of images that commemorates and celebrates the historic industries and workers of the region, made possible by a Library Services and Technology Act grant administered by the Illinois State Library. (http://www.pullman-museum.org/ihaccr/)

- Illinois Digital Archives (IDA) is a repository for the digital collections libraries and cultural institutions in the State of Illinois and the hosting service for the online images on this site. (http://www.idaillinois.org/)