The Pullman Building

You are at Home -> The Company -> The Pullman BuildingEarly Offices of the Pullman Company

Before the company town of Pullman was conceived, Pullman's Palace Car Company was still headquartered in Chicago. First located in the Tremont House at 92 Lake Street both before and after their February 1867 official charter [1], the firm moved in 1868 to offices at Randolph and the lake, a fortuitous move. Not only was the building close to the rail lines running along the lakefront, but a rail siding ran next to the building. On October 8, 1871, the Pullmans were at midnight awakened by the 'Great Fire.' George went to the office at half past one o'clock and remained until morning. [2] George's office went about eight o'clock. Nearly everything of value saved and brought to our house. Fire raged all day long. [3] The early morning hours of October 9 that Pullman spent in his office were used rescuing records and valuables from the company's offices, tossing them into train cars beneath the company's windows, and moving them over the Illinois Central tracks to stables at 18th Street where business presumably carried on. [5] Between 1871 and 1884, Pullman's primary offices were located on the east side of Michigan av. south of 18th st. and later in the old Peoples Gas building on the site of the present tall building of the same name. [7]The Commission

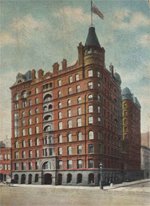

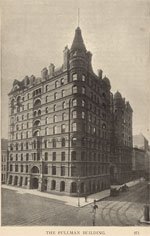

In 1883, with the second wave of building being finished in the Town of Pullman, George Pullman again commissioned Solon S. Beman's architectural services, this time to design an office building downtown. Instead of the Queen Anne or Second Empire styles Beman used in Pullman, or the Classical styles he would later use at the World's Columbian Exposition and in Christian Science churches in the 1890s, Beman for the Pullman Building was influenced by the Romanesque preferences of Louisiana-born architect Henry Hobson Richardson, architect of Chicago's Glessner House. [8] Constructed of red granite, brick, and terra cotta at the corner of Adams and Michigan (across from the Art Institute), the Pullman Building was a massive and imposing structure of 10 stories with turrets and a light well. Described by the Chicago Tribune, the design of the building would be a modification of the Norman round arched gothic, modernized and adapted to the peculiar [sic] purposes for which the building is intended, the main object being to give it an expression of dignified elegance in its simple massiveness. [9] As with all buildings built after the Great Fire of 1871, it was advertised as absolutely fireproof. [10] Excavation for the building foundations began in May 1883 [11]. In keeping with First Chicago School of architecture construction, iron beams and joists were used throughout the building; stairways were also of iron; it had four passenger elevators and a freight elevator and both gas and electric light. [12] In March 1884, the outer walls and brick work had been completed. Work came to a standstill as the Bricklayers' Union decided that the fifty or so tilelayers working on the tile floors and other interior work should demand $4.00 per day rather than the $3.50 they were receiving, and that they should strike if the employer refused the additional wages. The demand was made and refused, and the tilelayers unwillingly left their places and went home, leaving them, as they all contended, well pleased with their pay and disposed to fight the action of the union. [12a] The strike also affected work of carpenters and plasterers, so the Ottawa Tile Company issued a notice for non-union tilelayers which quickly were found and work resumed. [12b]Plans & Uses

The Pullman Building was designed for multiple use: the first floor for stores dealing in light merchandise, the second and third floors for Pullman offices, the fourth and fifth floors for Army Headquarters of the Division of the Missouri and for telephone company offices (Chicago Telephone Company and Central Union Telephone Company are noted in the floor plans), and the sixth floor for general office space. Beman's architectural offices were supposedly on the fifth floor. [13] The seventh, eighth, and ninth floors were reserved for residence suites of two, three, and four rooms, with private bath room, closet, hot and cold water for each. These suites are intended for use as bachelor apartments, and for occupancy by small families who wish to avoid the cares of house keeping. No cooking will be allowed in these apartments. [14] Provisions were made, however, for a restaurant on the ninth floor, with the kitchen and servants quarters on the tenth floor. The laundry, steam boilers and electric light generators were in the basement. [15] Separation between the offices and residences of the building were maintained by having separate entrances: offices could be accessed from Adams Street and residential apartments from Michigan Avenue. A light well was open from the glass roof at the third story.Floor Plans

Raves and Reviews of the Building

The Chicago Tribune in 1885 gave more detail on the involvement of various firms in the construction of the Pullman Building, to the tune of a thinly-disguised advertising "review" extolling its features. Here we learned that the- walls were of St. Louis hydraulic-press brick;

- that the enormous height of the ten stories could be ascended due to the perfection of the Hale hydraulic elevators;

- that the dimension stone underlying the foundation was provided by Messrs. Robinson & Co. with its closeness and firmness of grain unsurpassed;

- that the large glass and concrete roof was provided by the Concrete Illuminating Company;

- that no expense has been spared in making the entire structure thoroughly and perfectly fire-proof by the Pioneer Fire-Proof Construction Company’s system;

- that the steam heating was designed by Baker, Smith, & Co, and that four steel boilers of seventy-horse power each and about 500 radiators are used;

- that the radiators are exceedingly handsome in design, and the smoothness and the finish of the casting are especially noticeable…all of which are special characteristics of Detroit Steam Radiators;

- that the woodwork is not ordinary carpentry and that the hardwood furnished for the entire work [was] supplied by Messrs. Hayden Brothers;

- that hardware for the building in keeping with the other elegant appointments and furnishings of the building were supplied by Orr & Lockott (184-88 Clark Street);

- that the building was lighted with 2,200 sixteen-candle-power Edison lamps, that the dynamos and engines were in the basement, and that it was one of the largest and most complete plants ever placed in a single building in the United States, and supplied by the Western Edison Electric Light Company; and

- that the electric call bells throughout the building were supplied by the Western Electric Company of Chicago. [16]

An Odious Ode, An Egregious Elegy

Apparently, both the building and the elevators remained objects of wonderment throughout the years; in 1930, Chicago Daily News journalist Frank L. Hayes composed this odd verse in its honor:Pullman Building

There's an old historic building, which has stood for many years, And its name is intermingled with industrial careers It has frontage on an avenue where busy people shop And contains a host of offices, with tearooms at its top. I admire its massive pillars, its arches and its stoop; You will hardly find its likeness inside the changing loop, For its solid architecture is Victorian and grand Best, I like its elevator which ascends hand over hand, With its ornamental grillwork, all the wooden pins and knobs. Ah, some craftsman took much pleasure in those clever thingumbobs! It is furnished with large mirrors and a little red plush seat Where the ladies of the '90s sat and rested hidden feet. It is hoisted by a cable, which performs its work as well As the rope which hoisted buckets from an old moss-covered well. May no mood of innovation, stamping ruthlessly through town, Lifting sacrilegious fingers, pluck that elevator down.[17] In addition to penning this poem, Mr. Hayes had it somewhat wrong: the elevators were hydraulic, but responded to the tug on a rope by the elevator operator. [18]

Tenants

George Pullman had originally at least for publicity, and in a rationale similar to ones used for the company town of Pullman indicated that he wanted to furnish to the employés of the company who desired them living apartments of a superior character more convenient to their business…he says he will give them better apartments for less money than they can get elsewhere… [19] For several years after it opened, the Pullman Building did allow families in apartments, but some discord arising (and if anyone knows what that was, please let me know) it was determined to rent only to males of the most eligible character.[20] Pullman employee tenants included Vice President Thomas H. Wickes, Charles L. Pullman, a brother of George and Pullman contracting agent, and John S. Runnells, vice-president and future president of the Pullman Company.[21] Other famous (or infamous) tenants included utilities magnate (and then transit king) Samuel Insull; Allen B. and Irving K. Pond, brothers in architecture (Irving K. Pond worked in S. S. Beman’s offices); S. C. Pirie, of Carson, Pirie, Scott & Company in Chicago; H. E. Hooper, US publisher of the Encyclopedia Britannica; and Florenz Ziegfeld, future inventor of the Ziegfeld Follies.[22]Epilogue

The Pullman Company (so renamed December 30, 1899, several years after the death of George Pullman) remained in the Pullman Building until 1948, after which offices were moved to the Merchandise Mart.[23] By that time, all the adornments of the upper story-- the turrets, towers, and chimneys-- were gone. And, in a mood of innovation, stamping ruthlessly through town, the rope-operated hydraulic elevators were replaced during WWII with streamlined electric models.[24] Presumably, the War Production Board granted priority to the new equipment in part because of the 250 tons of scrap produced, less than the material used in the new elevator models.[25] The Pullman Building itself was demolished during a razing craze during the tenure of Mayor Richard J. Daley, along with dozens more buildings in Chicago’s Loop and thousands in Chicago neighborhoods with hardly a peep of protest.[26] The Pullman Building was replaced in 1958 with the Borg-Warner Building, an ugly anomaly among the Michigan Avenue cliffs in the Michigan Avenue Landmark District.Notes

- [1] Liston Edgington Leyendecker, Palace Car Prince: A Biography of George Mortimer Pullman (Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1992), 81.

- [2] Diaries of Mrs. George M. (Hattie) Pullman, quoted in Florence Lowden Miller, The Pullmans of Prairie Avenue: A Domestic Portrait from Letters and Diaries, Chicago History 1 (Spring, 1971), 144.

- [3] Ibid.

- [4] From the Log Cabin to the World's Fair 1803-1893. The Tremont House Hotel had the distinction of burning down five times in its history [see Stephen M. Davis, "'Of the Class Denominated Princely': The Tremont House Hotel," Chicago History 11 (Spring 1982), 27.]. The Tremont in which Pullman had offices was the third Tremont, completed in September, 1850 [op. cit.]. Chicago’s current Tremont Hotel is at 100 E. Chestnut off Michigan Avenue.

- [5] Miller, 144-5. See also Al Chase, Big Pullman Building Up for Lease, Chicago Sunday Tribune, February 8, 1948, Part 3, A.

- [6] A. T. Andreas, History of Chicago, From the Earliest Period to the Present Time. (Chicago: A. T. Andreas, 1886), V.2, 157.

- [7] Chase, Chicago Tribune, February 8, 1948, Part 3, A.

- [8] James R. Grossman, Ann Durkin Keating, and Janice L. Reiff, eds., Encyclopedia of Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 28-9. Online at http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/62.html. A number of First Chicago School architects were influenced by Richardson, including Louis Sullivan.

- [9] The New Pullman Office and Apartment Building, Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1883, 17.

- [10] Turner and Bond, Agents, Pullman Building sales brochure (Chicago: n.p., c. 1884), 4.

- [11] Tribune, May 6, 1883, 17.

- [12] Turner and Bond brochure, 4.

- [12a] The Tilelayers, Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1884, 8.

- [12b] Ibid.

- [13] Turner and Bond brochure, 5, 8-13.

- [14] Turner and Bond brochure, 5.

- [15] Turner and Bond brochure, 7, 16.

- [16] The Pullman Building, Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1885, 6.

- [17] Frank L. Hayes, Pullman Building, Chicago Daily News, May 14, 1930, 7.

- [18] Frank A. Smothers, The Truth About Elevators, Chicago Daily News, May 14, 1930, 7, 15.

- [19] The New Pullman Office and Apartment Building, Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1883, 17.

- [20] Many Notables Lived in Pullman Building in Olden Days, The Pullman News, June 1931, 47.

- [21] Ibid., 48.

- [22] Chase, Chicago Tribune, February 8, 1948, Part 3, A.

- [23] Ibid.

- [24] Philip Gunderman, Historic Elevators Due for Scrap Pile, Chicago Daily News, May 20, 1943, n.p. [clip from Pullman Company Archives, Newberry Library].

- [25] Ibid.

- [26] Richard Cahan, They all Fall Down: Richard Nickel's Struggle to Save America's Architecture (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1994), 11.

THE PULLMAN HISTORY SITE

Contributed by Kate Corcoran

Adams Street (office) entrance. Pullman Building sales brochure, c. 1884, Pullman Company Archives, Newberry Library.

Michigan Avenue (residential) entrance. Pullman Building sales brochure, c. 1884, Pullman Company Archives, Newberry Library.

Michigan Avenue (residential) reception area. Pullman Building sales brochure, c. 1884, Pullman Company Archives, Newberry Library.

Detail of arched north business entrance by photographer J.W. Taylor. Courtesy of the Faculty of Architecture, University of Melbourne.

General view of the Pullman Building, by J.W. Taylor, n.d. Courtesy of the Faculty of Architecture, University of Melbourne.

J.W. Taylor photo from James Wilson Pierce, Photographic History of the World's Fair and Sketch of the City of Chicago (Baltimore: R. H. Woodward and Company, 1893), 271.

Pullman Building, interior detail of 2nd floor entrance and open wells looking toward Office of the President (see 2d floor floorplan) by photographer J.W. Taylor. Courtesy of the Faculty of Architecture, University of Melbourne.

Pullman Building, north entrance detail by photographer J.W. Taylor. Courtesy of the Faculty of Architecture, University of Melbourne.

Other Pullman-Related Sites

- Historic Pullman Garden Club - An all-volunteer group that are the current stewards of many of the public green spaces in Pullman. (http://www.hpgc.org/

- Historic Pullman Foundation - The HPF is a non-profit organization whose mission is to "facilitate the preservation and restoration of original structures within the Town of Pullman and to promote public awareness of the significance of Pullman as one of the nation's first planned industrial communities, now a designated City of Chicago, State of Illinois and National landmark district." (http://www.pullmanil.org/)

- The National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is a 501(c)3 cultural institution. Its purpose is to honor, preserving present and interpreting the legacy of A. Philip Randolph, Pullman Porters, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the contributions made by African-Americans to America's labor movement. ((http://www.nationalpullmanportermuseum.com/)

- Pullman Civic Organization - The PCO is a strong and vibrant Community Organization that has been in existence since 1960. (http://www.pullmancivic.org/)

- Pullman National Monument - The official page of the Pullman National Park. (https://www.nps.gov/pull/)

- South Suburban Genealogical & Historical Society - SSG&HS holds the Pullman Collection, consisting of personnel records from Pullman Car Works circa 1900-1949. There are approximately 200,000 individuals represented in the collection. (https://ssghs.org/)

- The Industrial Heritage Archives of Chicago's Calumet Region is an online museum of images that commemorates and celebrates the historic industries and workers of the region, made possible by a Library Services and Technology Act grant administered by the Illinois State Library. (http://www.pullman-museum.org/ihaccr/)

- Illinois Digital Archives (IDA) is a repository for the digital collections libraries and cultural institutions in the State of Illinois and the hosting service for the online images on this site. (http://www.idaillinois.org/)