Labor and Race Relations

You are at Home -> Labor and Race Relations -> Pullman & the African-American ExperienceIntroduction

The story of the African-American experience and Pullman -- as employees of the Company, residents of the town, and consumers of passenger car services-- is a complex and in many ways a painful subject. This site cannot begin to do the topic justice in a comprehensive manner; rather, it is intended as an overview, a glimpse into what life was like to a person of color in the early part of the 20th century. The results of deep prejudice, endemic racism, and the South's reaction to Reconstruction virtually ensured that such a glimpse is rarely a happy one. Pullman travel was intimately linked with civil rights affairs throughout the 20th century. The landmark Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson 163 U.S. 537 (1896) involved a man travelling on a Pullman car. The ruling upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation even in public accommodations (particularly railroad cars), under the doctrine of "separate but equal." (from Wikipedia)The Company & Town

African-Americans had a complex relationship with the Pullman Company, the Pullman family, with Robert Todd Lincoln, who succeed George Pullman as president of the company. The Pullman Palace Car Company was appreciated for its commitment to hiring African-Americans and paying them in a fairly equitable manner. Many porters were fiercely protective of both George Pullman and later of his widow Harriet and Pullman's family. In 1920, the Pullman Company was the 4th largest employer of African-Americans in Illinois and the 2nd largest employer in the nation. A member of the board of the Pullman Bank, Robert Todd Lincoln became the second president of the Pullman Company, elevated to the thankless task of rescuing the Pullman Company from insolvency after Pullman's death. He performed this task with ruthless efficiency, making life difficult for Pullman porters and other passenger car personnel by inaugurating a wage system heavily dependent on tips.The Pullman Porter

The full story of the Pullman Porter is worthy of many exhibits. Suffice it to say that the Pullman porters had a hard, demanding, and frequently dangerous job dealing with a wide variety of problems. Porters were occasional targets of physical abuse, often suffered from verbal and mental abuse, and had to deal with "gun-toting lunatics", robbers, and accidents on top of the very difficult and never-ending tasks of their day-to-day responsibilities.

|

|

"Plea of the Pullman Porters" The Chicago Defender, December 31, 1910 |

"Cheap U.S. Senator" The Chicago Defender, July 31, 1909 |

"From Bandits" The Chicago Defender, November 23, 1912 |

"Railway Passenger Suddenly Goes Insane" The Chicago Defender, April 27, 1918 |

The Chicago Defender

The Chicago Defender, founded in 1905 by Robert S. Abbott, soon became the most influential news source for the African-American community. The Defender was a main voice in combating racial injustice. The paper's circulation was helped by Pullman porters and entertainers who distributed the newspaper south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Following years of boll weevil infestation, Jim Crow tenant farming, and economic collapse throughout the South, the Defender campaigned for blacks to migrate from the South to the North and was highly successful, tripling the black population in Chicago and other major cities in the North and Northwest in just 3 years. What became known as the "Great Migration" was a chance for better jobs and a better way of life for African-American families. Ironically, Southern leaders were at a loss to explain why African-American families would want to leave the oppressive and feudal conditions that existed at the time. The Defender also served as a way for Pullman Porters to keep abreast of each other, via John Winston's railroad-related social columns.

"In the Railroad Center" The Chicago Defender, January 21, 1911 |

"Sparks From the Rail" The Chicago Defender, June 8, 1912 |

Casual Racism

White America viewed people of color as inferiors, open to ridicule and scorn. Otherwise good and decent people would think nothing of portraying black Americans as cartoon-like savages and were entertained by broad, offensive popular portrayals. An example of this can be seen in popular music of the time:

Pullman Porter Blues. More sheet music can be found here. |

Pullman Porter March. More sheet music can be found here. |

Outright Prejudice

Casual racism easily spilled over into ugly and random violence and "Jim Crow" segregation laws designed to keep the races separated in Pullman car travel. The Chicago Defender is rife with stories of brutal and humiliating treatment south of the Mason/Dixon line, in Arkansas, and in Oklahoma.Who Was Jim Crow

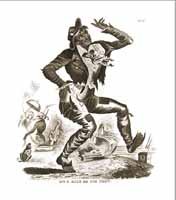

The term "Jim Crow" is used to describe the onerous segregation laws that arose after Reconstruction ended in 1877 and continued until the mid-1960s. The term "Jim Crow" actually began as a song, written by Thomas 'Daddy' Rice in 1828. Rice, a struggling New York actor, became rich and famous overnight by portraying the character Jim Crow, a highly stereotyped, cruelly exaggerated African-American character. Rice is credited with originating the practice of minstrel shows, appearing with a face blackened with cork on stages across America. By 1838, the term was being used as a racial epithet for African-Americans. Rice squandered his fortune and died in poverty in New York City in September, 1860.

Cover to early edition of Jump Jim Crow sheet music

Thomas D. Rice is pictured in his blackface role; he was performing

at the Bowery Theatre (also known as the "American Theatre") at the time.

Fighting Back

At some point, at different times, people simply had had enough-- of violence, inferior service, and humiliation. African-American porters and passengers alike began to chip away at the Jim Crow regulations; however, it wasn't until World War II and really not until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that the "separate but equal" laws, at least as they pertained to interstate travel on rail service and later buses, began to be repealed.

"Pullman Car Conductor Refuses to Jim Crow Mrs. Booker T. Washington" The Chicago Defender, April 22, 1911 |

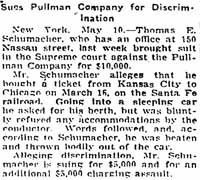

"Sues Pullman Company for Discrimination" The Chicago Defender, May 11, 1918 |

"Tipping -- An Evil" The Chicago Defender, February 3, 1912 |

"Story of Struggle of Pullman Porters" The Chicago Defender, January 5, 1929 |

THE PULLMAN HISTORY SITE

Other Pullman-Related Sites

- Historic Pullman Garden Club - An all-volunteer group that are the current stewards of many of the public green spaces in Pullman. (http://www.hpgc.org/

- Historic Pullman Foundation - The HPF is a non-profit organization whose mission is to "facilitate the preservation and restoration of original structures within the Town of Pullman and to promote public awareness of the significance of Pullman as one of the nation's first planned industrial communities, now a designated City of Chicago, State of Illinois and National landmark district." (http://www.pullmanil.org/)

- The National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is a 501(c)3 cultural institution. Its purpose is to honor, preserving present and interpreting the legacy of A. Philip Randolph, Pullman Porters, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the contributions made by African-Americans to America's labor movement. ((http://www.nationalpullmanportermuseum.com/)

- Pullman Civic Organization - The PCO is a strong and vibrant Community Organization that has been in existence since 1960. (http://www.pullmancivic.org/)

- Pullman National Monument - The official page of the Pullman National Park. (https://www.nps.gov/pull/)

- South Suburban Genealogical & Historical Society - SSG&HS holds the Pullman Collection, consisting of personnel records from Pullman Car Works circa 1900-1949. There are approximately 200,000 individuals represented in the collection. (https://ssghs.org/)

- The Industrial Heritage Archives of Chicago's Calumet Region is an online museum of images that commemorates and celebrates the historic industries and workers of the region, made possible by a Library Services and Technology Act grant administered by the Illinois State Library. (http://www.pullman-museum.org/ihaccr/)

- Illinois Digital Archives (IDA) is a repository for the digital collections libraries and cultural institutions in the State of Illinois and the hosting service for the online images on this site. (http://www.idaillinois.org/)